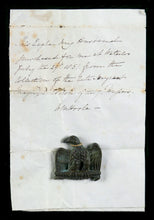

Waterloo Relic, French Imperial Eagle Fitting, 1815

Adding product to your cart

Overall: 31.5cm (12.5in) x 21.5cm (8.4in)

Cast bronze. Napoleonic era eagle badge, possibly for cartridge box or harness. Mounted on a 19th century notepaper backing bearing manuscript inscription ‘This Eagle my Husband /purchased for me at Waterloo / July 29th 1851. From the / collection of the late Sergeant / Major E Cotton of the 7th Hussars’, together with a paper label bearing manuscript notation ‘ French Eagle a spoil / found on the field / of Waterloo / 2s 6d E. Cotton’. Badge: 32mm x 33mm.

The present relic was purchased from the museum created by Sergeant-Major Edward Cotton (1792-1849), late 7th Hussars, who was a renowned Peninsula War and Waterloo veteran and an authority on the epic battle of 1815. After Cotton’s discharge from the Army in 1828, he settled at Mont St. Jean village on the Waterloo battlefield and soon established a reputation as a fine battlefield guide for the steady stream of tourists. He also built up a formidable knowledge of the battle from the many fellow Waterloo veterans who visited the site and published their recollections in 'A Voice from Waterloo'. His extensive collection of relics and memorabilia occupied a building at the base of the Lion Mound (built on the battlefield to commemorate the victory) became a must-see destination, with a pair of Napoleon’s silver spurs as one of its prized exhibits. The museum continued to be run after Cotton’s death until by his great-niece until its final dispersal in 1875.