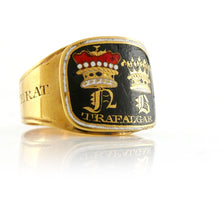

Viscount Nelson Duke of Bronte Mourning Ring, 1806

Adding product to your cart

Overall: 20mm x 19mm x 15mm (Size M)

Provenance:

The Matcham family

Thence by descent

Sothebys, Lot 58, The Matcham Family Collection, 5 October 2005

Exhibited

Formerly on loan to the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Gold and enamels. The black enamel rectangular bezel inscribed ‘TRAFALGAR’ and decorated with the Gothic letters ‘N’ and ‘B’ for Nelson and Bronté respectively surmounted by a viscount’s coronet and a ducal coronet; the interior further inscribed ‘Lost to his Country 21 Oct 1805 Aged 47’, and the outer shank engraved with Nelson's motto 'PALMAN QUI MERUIT FERAT' (Let him bear the palm of victory who has won it).

Read more

After Nelson was killed at Trafalgar, his executors, William, 1st Earl Nelson and J. Haslewood, arranged for fifty-eight gold and enamel rings to be distributed in his memory to thirty-one relatives and twenty-seven close associates including brother officers, lawyers and prize agents. The rings were produced by the London goldsmith John Salter (fl. 1802-1827) of 35 Strand, London. An original manuscript listing recipients of the rings, including friends, family members and fellow officers, survives at the British Library. Of these recipients, his siblings must rank amongst the most important. Nelson had a total of seven brothers and three sisters but at the time of his death only three were still living - The Rev. William who became the 1st Earl Nelson; Susannah, the eldest girl who married the coal and corn merchant Thomas Bolton; and finally Catherine (1767-1842) , the baby of the family and Horatio’s favourite.

In a letter to William, Horatio wrote of her in: “My small income shall always be at her service and she shall never want a protector and sincere friend while I exist”. However, she became well provided when she married George Matcham (1754-1833), for it was to prove a happy adventurous marriage. George belonged to a family who had made money in India. He was described by Lady Nelson as having a passion for travelling. He was charming, cultured, handsome and his chief outlet for energy seems to have been building, renting, exchanging houses all over Norfolk, Hampshire and around Bath. They had fourteen children. It is not with interest to note the time frame between the Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805); the first news of Nelson’s death in England (6 November); and journal entry of Nelson’s nephew George Matcham (1798-11877) recording the delivery of his Nelson ring (25 November) - “Colonel Coehoon came down from London...brought my Mourning ring. Very Handsome.”

It is difficult to appreciate today the symbolic significance of the victory at Trafalgar to the British nation in 1805. Nelson was worshiped as a secular deity, the saviour of the nation. His victory guaranteed British control of the seas and created a global maritime power that endured unchallenged for over a century. Despite persistent seasickness, his career flourished as he moved from ship to ship in the East Indies and the Caribbean, showing a flair for naval strategy. He became one of the youngest captains in the Royal Navy. He saw active service in the American War of Independence, in the wars of the French Revolution and in battles in the East Indies, the Caribbean, the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.

Before the battle of Trafalgar, Nelson made his famous signal to the fleet: ‘England expects that every man will do his duty. ’ He received his fatal wound as he paced the quarter-deck with Captain Hardy. A French musket ball struck the epaulette on his left shoulder and penetrated his chest. He fell face down on the deck. Hardy was a few paces ahead and to his right. On turning round he saw Sergeant Major Secker of the Marines and seamen raising Nelson. When Hardy expressed the hope that Nelson’s wound not too severe, he replied: "They have done for me at last, ... my backbone is shot through." Carried below to Victory’s orlop deck, he lived just long enough to hear the news of the surrender of more than a dozen enemy ships, permitting him to utter “Thank God I have done my duty." When the news of his death reached England, the King wept, as did thousands who lined the route of his state funeral on 9 January 1806.

From the ‘Nelson Companion’ by Colin White, Former Director of the Royal Naval Museum.

‘However, the most available precious commemorative is certainly a ring. Nelson rings fall into two broad categories: mourning and commemorative. The best made and best recorded mourning rings were family rings issued by Nelson’s executors after his death. Fifty-eight of these rings were the family rings issued by Nelson’s executors after his death. Fifty-eight of these were made by John Salter, a silversmith in the Strand much patronised by Nelson and from whom he bought a number of personal items, including Horatia’s silver gilt christening cap now displayed in the Royal Naval Museum.

‘A few of the rings, a very few went, went to the late Admiral’s famous contemporaries, notably to Captain Hardy who carried the Banner of Emblems at the State Funeral and who, presumably, wore the ring to the sad event. But the majority were genuine ‘family’ rings and were distributed to a variety of relations in the Matcham and Girdlestone families. In 1915 an excellent article was published dealing with the making of these rings and listing their recipients, and I have in the past decade attempted to track down their current locations, but with little success. So far I have managed to identify to identify only fourteen of the fifty-eight. And I am not at all sure that one at least of these fourteen may not be the same one surfacing twice! However, Dr Goulby, in a most interesting contribution to the Genealogists’ Magazine in June 1990, lists not only the eleven now in museum collections, but also has done better than I in identifying thirteen in private hands.

Strictly speaking, these rings are not commemorative at all, since they were not made for general sale and were available only to a selected band of owners. They fall, perhaps, into category of personal memorabilia …’

Further reading: Rina Prentice, The Authentic Nelson, (2005), p. 174